The Inner Life of Climbers

The Boys of Everest: Chris Bonnington and the Tragedy of Climbing’s Greatest Generation, Clint Willis, 2006

In the current playgrounds of their sport, mountaineers learn what primitive people know instinctively – that mountains are the abode of the dead, and that to travel in the high country is not simply to risk death but to risk understanding it. Robert Reid Mountains of the Great Blue Dream

Books on climbing normally focus on the adventure, achievement, clashes among climbers, and tragedy. Or more recently, on the commercialization and destruction of the “extreme” sport where, for enough money, practically anyone can have an oxygen mask strapped on and be carried to the top of Everest. Good works exist on the lives of Anatoli Boukreev and Tenzing Norgay Sherpa and his family. But getting to know the climbers and what goes on in their heads in less common. It is precisely this inner dimension that Willis is adept at describing. During Bonnington’s first time on the Eiger Willis narrates:

He (Bonnington) took an hour to climb 60 feet. Ian (Clough) from time to time peered up at him and saw the rope still hanging free. They both knew that a slip here would kill them, but Chris knew this like a piece of news or history he couldn’t manage to believe. He put it well aside and got on with standing just so or tugging cautiously at a hold; his mortality shrank to a concept. And still his knowledge of the risk colored every action he performed, lending his movements and the stillness between them a deliberate and serious quality that awoke his desire for peace, for clarity.

On the direct Eiger route named for John Harlin who fell to his death when a rope broke, Willis writes:

Dougal (Haston) felt himself flotsam on the surface of something vast and deep…John’s death was a part of that dark scenery. Dougal felt a sense of urgent gratitude, almost painful in its intensity; he was alive with this task to perform…Dougal felt his isolation on the face. He liked the Germans; they grieved for Harlin without falling apart or expecting anyone else to do so. But Dougal was not like them…He could ignore the cold as well as his own spasms of grief and fear and the odd and somehow unfinished fact of John’s death. He would finish the climb whatever anyone else might choose to do.

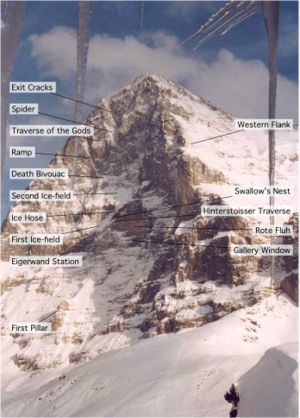

Eiger North Face

Eiger North Face

Willis’ book includes an inner life account of the remarkable climb of Annapurna’s south face by one of the greatest teams of climbers ever assembled. To understand this feat compare it to the north face of the notorious Eiger which has a summit of 13,000 feet and is about 5900 feet above the valley below. Annapurna’s south face starts at about 17,500 feet and extends to the summit at 26,545 feet. Most of the climb is in the death zone.

Climbers killed on Annapurna include famed Russian climber Anatoli Boukreev in 1997 and Christian Kuntner in 2005.

Annapurna’s Anatoli Boukreev Shrine

Annapurna’s Anatoli Boukreev Shrine

Climbing in the Himalayas there is always the altitude, the thin air. Willis writes:

Peter (Boardman) was feeling the altitude without knowing it and he lost himself in games, in the twisted logic of dreams. He named the various knots cows and thought of the pitons as Americans. He gave a girl’s name to each of the carabiners that dangled from his waist.

After Doug Scott, Peter Boardman, and Joe Tasker had summited sacred Kangchenjunga, Willis writes:

They had been afraid to die on the mountain; now they feared a return to a world where such matters were misunderstood, where people thought dying mattered more than it did. They were afraid to leave behind the clarity of intention that had possessed them here. They were afraid not to know what to do. They felt uplifted and unworthy at once — they were drunk with confusion and joy and anxiety. They had come here and retrieved something. They worried that they couldn’t protect it, that they hadn’t changed and that they would forget.

Kangchenjunga

Kangchenjunga

Completing this work featuring climbs from 1958 to 1985, the reader is surprised to realize that almost all of Boning ton’s boys have been killed in the mountains, one or two at a time. For each death, Willis imagines and narrates the last moments; what was the climber thinking as he fell, was buried, or simply quit. The most surprising account is the death of Peter Boardman, perhaps the strongest of all Chris’s boys at high elevation. Peter was climbing the northeast ridge of Everest with Joe Tasker in 1982, who had already suffered two strokes earlier in the climb. Willis posits that Joe slipped, caught himself, and suffered a final massive stroke which killed him. Willis speculates that Peter sat down briefly to grieve and never got up again. Peter’s body was found on the northeast ridge in 1992.

Chris Bonnington finally summited Everest for the first time in 1985 at the age of 50. Willis wryly notes that Chris had any number of Everest ghosts to help him up.

The tragedy of the title seems not so much all the deaths, although they are certainly tragedies for the families left behind, but that these young men cannot imagine life without the challenge of the climb; the new mountain, the new route, the lighter expedition. They keep returning until they die.

Their ever smaller teams of two to four climbers and Alpine style fast ascents without supplemental oxygen predicts the arrival of Anatoli Boukreev in the next generation; the solo climber able to tackle up to four 8000 meter peaks each season with virtually no equipment or support. And like them, Boukreev continues to return till his death. He simply can’t imagine any other life.

Grumble: Book editing is steadily deteriorating today and this book reaches a new low with entire sentences truncated or repeated on the next page (photo insert). The blame probably rests with an increased dependence on computer typesetting and grammar checking unaided by human proofreaders. The human reader doesn’t really need this added challenge.

Annapurna South Face, Chris Bonnington, 1971

Bonnington wrote this account and took most of the remarkable pictures in the book. Perhaps most remarkable is the folded photo in the back of the book of the south face with the climb route, camps, and elevations shown.