Consul on the Canals

Monday, June 25th, 2007Gestures, H.S. Bhabra, 1986 (reprinted 2003)

This is the only novel written by Bhabra, who died at the age of 44 in 2000. Written as the memoirs at the end of his life by an octogenarian diplomat for his grandson, the novel is strangely reminiscent of the novel (and film) by fellow Asian Kazuo Ishiguro Remains of the Day.

Bhabra was born in Bombay India in 1955, Ishiguro in Nagasaki Japan in 1954. Both emigrated as young children and were educated in Britain; Bhabra at Trinity College, Oxford; and Ishiguro at the University of Kent with a Masters from the University of East Anglia. Both novels are set in the same Historic period from the rise of Fascism and Nazism in Europe to their fall and eclipse after WWII. Both authors write with a more nostalgic, distinctly British voice than almost any of their contemporaries.

The Central character in Remains of the Day is a servant, Stevens, a butler whose only purpose in life is to run the perfect household for his Lord Darlington, a Nazi sympathizer. The central character in Gestures is a civil servant, Jeremy Burnham, a career diplomat, self described as:

… an Englishman of the upper middle class which is to say… one of the most complete creatures of convention the infinitely various human race has so far succeeded in producing.

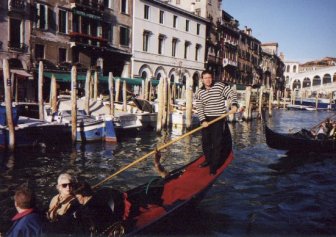

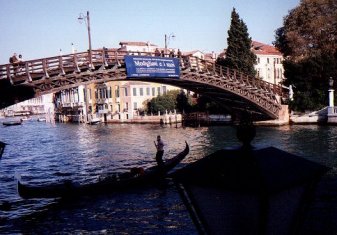

Gestures opens with Burnham’s first posting as Assistant Consul in Political backwater Venice in 1923 just as Mussolini is coming into power in Italy. Burnham proves himself as a “Dependable Man” negotiating with the fascist chief of police to classify the murder of a British subject (a wealthy woman) as a death by natural causes allowing the British Jew who would have been framed for the murder to leave Italy, and allowing the likely murderer, a pro fascist British man, to be protected by the fascist police. As his reward, Burnham is promoted to Consul, replacing his academic and morally conscientious boss who had wanted to seek real justice for the crime.

Burnham marries, has children and a series of successful postings including Riga,capital of Latvia on the Baltic, and Peking before spending WWII in London assisting European governments in exile. His wife and one of his two sons are killed in the war. After the war, he is posted to war devastated Amsterdam as Consul with the job of restoring British Dutch trade.

In his job he meets a powerful private Dutch industrialist who grew his fortune by trading between Germany, France, and Britain during WWI, and who retained and ran his empire throughout WWII. Faced with evidence that the industrialist assisted in providing Dutch Jewish laborers for forced labor factories in Poland, Burnham must decide whether the industrialist should be tried for war crimes or be allowed to run his businesses as the British government wants.

We now untangle the story of the people Burnham first encounters in Venice. The Jewish art historian Dr. Anthony Manet, saved by Burnham in Venice in 1923, is hired by the Dutch industrialist to authenticate a Rubens painting. He emerges as a central character in the novel. A multicultural Jew whose ancestors were Venice traders, Manet knew many of the culturally influential Jews of Europe including Freud. Financially secure, he escapes the Holocaust by moving to the United States. He gives an eloquent statement on the fate of the Jews of Europe:

I came from a peculiar people, and I was born into an interesting time. It seemed possible the old squabble of race of creed and race might be forgiven. It seemed we might be men.

We (the Jews) came close to being the dream of a Europe without borders. We traveled and studied where we wanted. We shared our information. We offered each other hospitality. Perhaps that was where we went wrong, where we became misguided. We, in our very persons, were evidence that Nations were only an administrative convenience, of no real relevance to an international community. It has taken two world wars to prove us wrong. We believed it was possible to be human, simply human, without the atavistic necessity to belong. We had a strange apocryphal vision of the world. We said we would light such a candle of understanding in its heart as would never be put out, but it is we who have been extinguished.

Burnham marries again and has more children, yet stubbornly hangs on to his class prejudices and learns little during his life in remarkable times. Still, he senses a shortcoming in others today:

The young of my class and even, increasingly their elders, all children to me, begin to offend me. They know so little. They are so small, so stupid, so arrogant, empty and assured, without even the wealth or empire which gave us our assurance. They travel without tasting. They look but do not see. They do not realize it, and if they did, they would dismiss it as the raving of a foolish, fond old man, but they look ridiculous.

Bhabra had a serious writer’s block most of his life, yet he wrote the elegant and complex Gestures in only five weeks. He developed a strange obsession with climbing bridges in the 1990s, getting arrested while attempting to climb the Golden Gate Bridge in San Francisco. A week before his 45th birthday, he killed himself by jumping off the Prince Edward Viaduct on Toronto’s Bloor Street.