Greed Hall of Infamy

Age of Greed, The Triumph of Finance and the Decline of America, 1970 to the Present, Jeff Madrick, 2011

Madrick begins his account around 1970 when CEOs made an average of 12 times the compensation of the average worker and bankers were paid less than the CEOs of major non banking corporations. Today the CEOs make 200-300 times the average worker and CEOs of finance companies can join the ranks of the top 400 wealthiest Americans, far outreaching the wealth of the average CEO. This 40 year period also saw the greatest decline in American industrial innovation and research in history. He tells the story of this decline through the careers of the most notorious characters of the period.

Citigroup’s Wriston, Inventor of Too Big to Fail

He starts with Walter Wriston, who headed what later became Citigroup from 1967 through 1983 as it became the first “too big to fail” financial institution. Writon worked tirelessly to undermine, eliminate, or circumvent all banking regulation while repeatedly requiring the Federal government to come to his rescue when his bank got into financial difficulties. During his tenure, state usury laws were eliminated, the limits on interest banks could pay depositors were eliminated, and the prohibition against interstate banking were eliminated. Both Carter and Reagan were responsible for these banking changes.

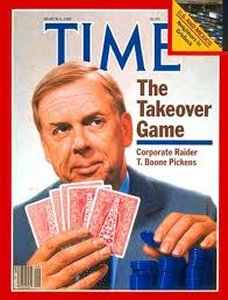

Pickens, Greenmail specialist and Milken, junk bond specialist

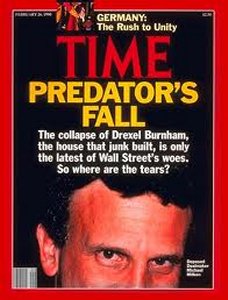

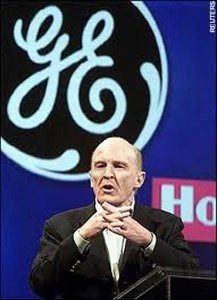

He then moves to the aggressive acquisitions and mergers period of the 80s highlighting such innovations as insider trading (Ivan Boesky), greenmail, the launching of a fake bid to buy a company to induce other bidders to enter a bidding war. T Boone Pickens repeatedly used greenmail launching bids without ever completing a company purchase building enormous wealth in the process. He uses GEs Jack Welsh to illustrate that acquisitions with no strategy other than maximizing profits and driving up the price of the company stock. Welch perfected the art of manipulating accounts to show increased profits every quarter for 13 straight years. In the process GE shed hundreds of thousands of jobs, closed countless divisions, and moved GE steadily toward becoming a financial giant accounting for more than half of GEs profits. To provide money for all these acquisitions, Michael Milken perfected the junk bond, a way to raise money from investors outside normal financial regulations. Milken was brought down, not from abuses in junk bonds, but because he began to illegally “park” stock purchases for those quietly buying stock in a target company above the 5% disclosure limit.

Welch strips GE and exports jobs

He illustrates how destructive acquisitions have become to the companies involved and to the overall economy. The goal is to become the dominant player in a field after which reducing labor and research (innovation) can be used to drive profits without fear of competition. The consumer and the economy as a whole suffers. The biggest example comes out of the mergers in media, cable, and entertainment with the mergers of Warner, Time, Turner, and AOL which destroyed enormous wealth and turned the unique 24 hours news CNN network into a news-less shell.

After junk bonds became a dirty word and helped to bring down the entire S&L industry, the new hot investment vehicle became the hedge fund. Hedge funds are limited to 100 very wealthy investors. He uses George Soros, who claims he never broke the rules with his investing then admits that there were no rules, and John Meriwether of LTCM who introduced the VAR volatility measure and hiring of mathematical “quants” to the business of risk managed investing. LTCM collapsed in 1998 but Soros is still going strong.

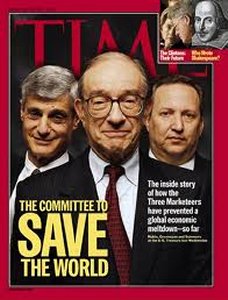

He returns to Citigroup with CEO Sandy Weil, illustrating the nutty progressing of acquisitions and divestitures. Weil came by way of Shearson merging with AMEX who when acquired by Prudential. Weil then bought back Shearson from AMEX and bought Travelers. Weil then merged with Citi to form Citigroup. The only problem was the Glass-Steagall separation of investment from retail banking. Weil approached Alan Greenspan who offered a two year waiver to allow the merger and a year later Glass-Steagall was history. Citigroup continued its various flirtations with disaster, coming to the brink of collapse time after time only to have the government rescue it. An early colleague of Weil, Jimmy Dimon followed his own circuitous route to eventually head JP Morgan.

He then leads us through the corrupt world of stock analysts, featuring Frank Quattrone, and IPOs leading to the dot com crash of 2000. By 2000 virtually every analyst was recommending buy or strong buy for every new stock issue. A hold or sell meant simply that the analysts company had been cut out the commissions involved in the IPO. Allocations of IPO shares was a rewards – punishment labyrinth of conflicting interests. Hundreds of billions were lost as the companies folded in the crash. Similar things happened in communications with analysts like Jack Grubman pushing Worldcom, Global Crossings, Tyco, and Adelphia stocks ever higher. To add to the mix, accounting giant Anderson, was approving the crazy accounting of companies like Worldcom and Enron. Banking giants were also using “creative accounting” to show profits and hide losses or risky exposure.

Finally he turns to the current mess featuring Bear Stern’s Jimmy Cayne, Lehman Brothers’ Richard Fuld, Merrill Lynch’s Stan O’Neil, and Citigroup’s Robert Rubin. Derivatives for currencies, commodities, and other securities have been around since the 1960s and were applied to mortgages by Fanny Mae in the 1980s but for conventional or conforming loans only. Dividing securities into tranches or slices to tailor risk and insuring derivatives have also been around a while. What was new after the dot com crash was that mortgage backed derivatives became the new best way for financial institutions to earn huge fees. Everyone from Freddy and Fannie, to Wall Street, to the banks, to the hedge funds all jumped on board, creating an enormous demand for new mortgages. The only way to meet this demand was to create new types or mortgages (ARMS, interest only, pay what you can) and sell them to an ever wider collection of consumer. Enter specialized mortgage firms like Countrywide under Angelo Mozilo. When the quality of mortgages started to get B ratings, ever creative geniuses of finance created the CDO 2 which was made up of B rated derivatives somehow magically transformed into AAA instruments.

Estimates put the federal exposure to mortgages backed by government guarantees at $12 Trillion, too big to fail on steroids. Despite TARP and institution bas debt writedowns in the hundreds of billions, we still don’t know the extent of toxic assets still sitting on the books. Madrick is particularly critical of the failure of government not to insist that the books be cleaned and the institutions forced to lend to business and consumers as a price for the bailouts. He also thinks the government should have been better compensated for the extreme risks the public took. He doesn’t however call for a breakup of the too big to fail finance organizations.

There are excellent books covering specific periods and incidents covered here but the primary benefit of this work is to pull together a 40 year overall look at the transformations of American business and finance. His conclusion is that the entire period is one of wasted opportunities and massive loss of wealth that could have been used to build a better, sustainable America. From the Latin American loans in the 1970s to the destructive acquisitions binge of the 1980s via junk bonds and the collapse of the S&Ls to the telecom bubble of the 1990s to the technology bubble of 2000 to the mortgage crisis of 2008, trillions of investment dollars were simply flushed down the toilets. Some of that enormous investment found its way into the pockets of a handful of very wealthy investors which was the driving motive for all the investment activity in the first place. In the process, finance became the new way to wealth in America, replacing entrepreneurship and innovation. He sites a study that shows that Harvard graduates now going into finance can expect to earn three times more than their classmates.

In a heavily and properly regulated environment, none of this need have happened but every President from Carter on has led to more and more deregulation. Obamas efforts at reform fall far short and Madrick is pessimistic that government is up to the task to putting into place an adequate regulatory environment.