Brahmin Faker

The World Is What It Is, The Authorized Biography of V.S. Naipaul, Patrick French, 2008

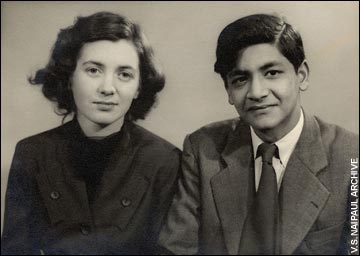

V S Naipaul with Nadira and Nobel Prize 2001

This 500 page biography combines a detailed, almost reverent consideration of the extensive writings of Sir V.S. Naipaul (Vidia), together with an honest account of the caustic, selfish, exploitative, egotistic life of the man. Much space is devoted to the weird love-hate relationship between Vidia and the younger American author Paul Theroux (Mosquito Coast) who he met in Uganda in 1966. Theroux himself wrote several accounts of the life of Vidia but French considers Theroux’s mixture of fact and fiction unreliable and heavily biased by the strange relationship including the one sided correspondence in which only Theroux contributes.

Vidia remained in near poverty for much of his writing career, often supported by his English wife, the saintly Pat, whom he continues to mistreat until her death from cancer. Only when he changed agent’s after the publication of his masterpiece A Bend in the River, did his income increased 8 fold making Vidia financially secure for the first time in his life. Until this change in agent, he remained one of the poorest paid authors of his stature anywhere, earning far less than the successful Theroux. After publishing A Bend in the River, Vidia declared novels to be a dead form although he continues to write them, and concentrated on writing Tocqueville-like travel works for which he receives lavish up front fees allowing him to travel first class anywhere in the world.

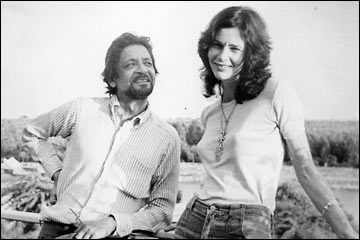

French saves his most devastating account for the end, when Pat is left alone dying of cancer, while Vidia travels to Indonesia to join his long time mistress (24 years), the Argentine-British Margaret Gooding, and begin research for Beyond Belief: Islamic Excursions among the Converted Peoples. Vidia sends Margaret home while he travels to Pakistan where he meets a 38 year old Muslim divorcee Nadira. He knows Pat is dying and Margaret in now aging, so he seduces Nadira. Nadira arrives in London the day after Pat’s funeral and they are quietly married. Nadira scatters Pat’s ashes in the countryside. Margaret learns that Vidia is married from the newspaper. This book should come with a warning to feminist readers.

Some of the most interesting parts of this book are the treatment of the British colonial era in India and the creation of indentured servitude for Indian workers recruited for labor in Fiji and Trinidad-Tobago. According to French, the Indian caste system varied from region to region and was quite dynamic until the British colonial occupation when the British rigid concepts of class transformed the Hindu caste system into an equally rigid system with real class implications. Under the British rule, caste came to matter greatly.

It is then hardly surprising when some of the indentured Indian laborers transported to a new world chose both to change their names (some choosing ridiculous names like Maharajah) and their castes in the process of beginning a new life. French believes this to be the case with the Naipaul family, who chose to claim that not only were they Brahmin, but that they were pundits (literate with a reading knowledge of Hindu religious texts) as well. Naipaul’s family was headed by an imperial grandmother (called Queen Victoria behind her back) who pushed the family to acquire land and an education. Vidia understood well that education and competing for one of the few available colonial or missionary scholarships was the only means to escape the small limited islands for a larger life. Several of his siblings were also able to gain scholarships and escape to study abroad.

While his education was totally British in a Trinidad colonial school and at Oxford with only a primitive, largely superstitious, understanding of Hindu concepts, He clearly understood the value of creating a Brahmin myth for himself, inventing a unique fish based vegetarianism he later used to terrorize British hosts by walking out of invited dinners if he found the food to his dissatisfaction. He also used his phony caste to avoid any work or labor at all including such minor household chores as making the bed to picking up after himself. A slavish wife or other woman became essential to maintain his domineering lifestyle.

A central theme of his work remained the impact of cultural imperialism on native populations and indigenous culture. Early this meant the impact of the British on Indian and other Caribbean and African cultures, but later was expanded the include the conversion of non Arab cultures (Iran, Pakistan, Malaysia, and Indonesia) to Islam. He treats the pernicious effects of these foreign cultures on the indigenous cultures as permanent and negative, ignoring the obvious fact that the Islamic conversions happened more than 1,000 years ago.

Yet, by his behavior, it seems that Vidia himself desired nothing more than to become an Englishman, at one point giving up his Trinidad passport and accepting a knighthood from the Queen. Vidia is seen in this authorized biography as a very complex and difficult man.

At more than 500 pages, the biographer can spend several pages digging out the truth of what happened at a dinner party for which Theroux wrote an account that French finds to be fictionalized. Maybe we could have been spared a little detail.