Economics Debunked

The Predator State, James K. Galbraith, 2008

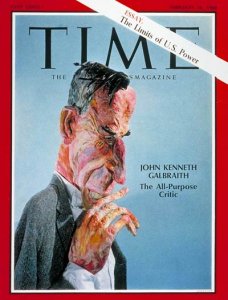

James Galbraith’s father John Kenneth Galbraith (The New Industrial State 1967), in 2006 from his deathbed, suggested that James write this book. It was published in the spring of 2008 before the total meltdown of the financial system threw the economy into a downward spiral whose bottom we have yet to see.

Both Galbraiths are Keynesian economists, those forgotten guys. The basic tenet of Keynesian economics is that only aggressive government policy can stabilize the economy which is otherwise subject to massive swings, creating enormous problems such as run away inflation, failing financial institutions, failing corporations, and massive unemployment. But, hey, today everyone in Washington is a Keynesian, right? After forty years of Chicago school dominance, Keynes is back.

James Galbraith outlines a history of the world economy starting with the Bretton Wood Conventions following WWII which established the U.S. economy and the gold backed dollar as the standard on which all foreign currencies would be based. The breakdown of this system, started when Nixon went off the gold standard and allowed the dollar to float, provides the backdrop to a consideration of the major economic theories of the conservatives advanced to fill the void left by the abandonment of Bretton Wood; monetarism, supply side economics (with trickle down), balanced budgets, and free trade. Even the Democrats became advocates of balanced budgets and free trade.

One by one Galbraith exposes these theories to be false with no empirical evidence. Unlike Kline’s Shock Doctrine, which portrays Milton Friedman and his colleges as co conspirators in a massive transfer of wealth, Galbraith, who remains friends with some conservative economists, views them as benignly misdirected, living in their ivory towers where they consistently ignore the facts.

While the Presidents from Reagan through Clinton felt the need to incorporate conservative economists into their administrations to give a veneer of academic respectability, George W Bush felt no such need and simply appointed cronies who poured the public coffers directly into the pockets of lobbying client firms without any resort to economic theoretic justification.

Today there is open discussion of the role of Alan Greenspan in the current crisis. There is no corresponding discussion or remembrance of the role of his predecessor, Paul Volcker, who held interest rates at rates as high as 20%, ruining the economies in much of Africa, Asia, and Latin America who had borrowed heavily from the Chicago school dominated IMF who insisted on shock therapy changes as a condition of their loans. Unsurprisingly the struggling countries were unable to pay off the loans at the new extortionary levels. This led to a collapsed overseas markets for American products and to greatly strengthening the dollar, permanently weakening steel and auto production in the US as it was unable to compete with cheaper products from Germany and Japan. Galbraith points out that inflation is another thing economists are unable to understand or control. It seems to appear and disappear out of nowhere.

Galbraith attributes the fall of the Soviet Union largely to their inability of pay off their massive loans in an environment of super high interest. The rise of China and India as an economic powers was made possible precisely because they did not borrow heavily from the IMF or adopt shock therapy.

What actually ended inflation in 1984 was the incoming flood of foreign investments looking for high returns from the interest rates and the stability of the American government. It had nothing to do with monetarism, the supposed justification for the extortionary interest rates. Yet, worryingly, this same Volcker has been named to the new Obama economic team, presumably because of his “expertise” in fighting inflation. Lord, save us from the experts.

One concept, that of the free economy, Galbraith points out is without any meaning at all except perhaps to very large multinational corporations, yet all politicians who hope to be successful must pay lip service to it just as they must attend church even though they may be atheists. In the real world, free markets are so rare, they are almost non existent.

Galbraith points out when the Japanese real estate and financial bubble burst throwing that country into a decade long stagnation:

This dimmed the luster of the Japanese model for American observers, even as they largely overlooked the obvious point: there is evidently no development path that an unfettered, liberated, free capital asset market cannot screw up.

On the relationship between full employment (deemed by conservative economists to be inflationary and therefore bad) and wage inequality, Galbraith demonstrates, as do all Keynesians, that full employment, such as is enjoyed in Denmark, actually leads to greater wage equality, not less, and there is no evidence that full employment is inflationary.

Getting into the book’s central theme, he then makes some original observations along the lines of the Black Swan phenomenon. The big dominant corporations such as ATT and IBM lost their technological leadership to small startup entrepreneurs who were funded by new venture capital and equity raising wall street firms. The founders of these firms in Silicon Valley, Seattle, Boston, and other technology hubs overnight became extremely wealthy together with their supporting financial institutions.

Traditional companies became dependent on technology from outside rather than developing it internally and the CEOs of these traditional companies became extremely envious of the great wealth of these new technology usurpers. The CEOs formed closed groups, gained control of boards of directors, and demanded and received compensation and bonuses to close the gap with their entrepreneurial counterparts at levels unsustainable by the companies they ran. In a word, these CEOs became predators, preying on the companies they supposedly were leading (down the drain).

This group did not come from within their companies but were outsiders with little technical knowledge of the company. Their primary justification for their compensation was that they had been CEO of other firms where they were paid outrageously. As a new and small elite, they became predators, feeding off and destroying stockholder value and even whole companies as they competed with other CEOs to maximize their own compensation. They measured their own success and worth, not by the success of the companies they were failing to lead, but by their accumulation of personal wealth. Where did this loot go? Not into the productive economy, but into private mansions and conspicuous consumption.

Galbraith attributes the decline of the modern American industrial system studied by his father to:

These four phenomenon — the rise of trade, the reassertion of financial power (wall street and venture capital), the outsourcing of technological development, and the ascendancy of an oligarchy in the executive class — … had dramatic effects on American industrial corporations, on the way they are run, and on their broadly declining position in the world.

On the need for and desirability of regulation:

…Regulation helps the competitive position of relatively advanced businesses, by reducing or even eliminating the competition from backward enterprises that offset higher production posts with less safe factories and products and will lower wage bills.

Unfortunately for America the advanced “better” businesses of today are often offshore like the Japanese automakers.

Galbraith considers the rise of predator executives not to be a part of the normal process of growing wealth disparity, but a separate and more pernicious phenomenon. Not satisfied to raid and bankrupt their firms, this group set out to control and dominate the government and its apparatus as well. They are not normal conservatives, desiring a smaller government; they want a strong government, led by an imperial executive branch, in position turn a blind eye to regulation, to privatize as many government functions as possible with extortionary contracts, but also to be ready to bail them out when their destructive practices bankrupt their companies. By controlling government, they can minimize governments regulatory oversight that may interfere with their predatory practices while assuring that the government is ready with contracts and bailouts when needed. Hence the phenomena of Cheney turning the executive, and Newt Gingrich, Tom Delay, and Jack Abramoff turning the congress into the arms of the new predator state.

…it is fair to say that the very concept of a public purpose is alien to, and denied by the leaders and operatives of this coalition.

Modern corporate decision-making structures exist … to permit senior executives to do what they want… This is the culture that Richard Cheney brought back into government… The operational result is a government by cliques operating in secret, indeed with their very membership unknown outside…We have instead (of checks and balances) a government public relations apparatus whose purpose is not to persuade but to deflect, deter, and frustrate inquiry into the operation of the government…It fills the courts with functionaries who are prepared to act as enablers for the executive branch.

But if the government is predatory, then it too will fail in every substantial way (just like the corporations). Government will not cope with global warming, or with Hurricane Katrina, or the occupation of Iraq, or Election Day chaos, or avian influenza, or nuclear weapons…Failure on that scale is not due to incompetence. It is intended. Inside government no one cares. The attention of the people in charge is focused on other goals (acquiring massive personal wealth).

So, can the predator state be turned around under an Obama Presidency to tackle current problems like global warming, broken health care, a financial meltdown taking more and more companies with it? Galbraith hopes so but recognizes how broken government is, how far down the predator path we have gone.

Galbraith ends with discussions of the need for reestablished regulation and the re institution of utilities where free markets do not exist (like California and Texas electric power), the need for massive new levels of government planning and investment to rebuild infrastructure, provide public services like education and health care, and to tackle really tough problems like CO2 emissions and global warming. He pleads for the reestablishment of standards for safety, working conditions, minimum and maximum income and the environment. We also clearly need new standards for financial markets and energy and global trade. Galbraith remains confident that America will be able to pay for all these reforms and recover its global leadership position as an innovative, moral, economic power.

This book is a compact 200 pages. It would have been helpful to provide more detail and facts to debunk the conservative’s economic theories, but maybe Galbraith thought too much detail would discourage readers.