Anton Chekhov

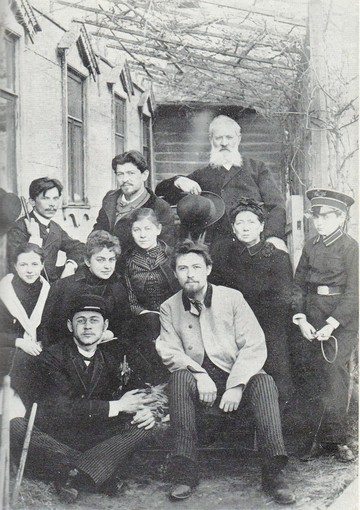

Anton Chekhov  and his brother

and his brother

Book Review: Treasured memories of a beloved brother

‘Anton Chekhov: A Brother’s Memoir,’ finally translated into English, offers a gossipy remembrance of a beloved brother by a man who continues to miss him.

His short stories, plays and journalism are still upheld as models of humane perception and imaginative compassion. That their short fiction is “Chekhovian” is the compliment we pay to contemporary masters such as Alice Munro and William Trevor. No month goes by without a performance somewhere of “Uncle Vanya” or “The Seagull” or “The Cherry Orchard.” Chekhov’s admirers are legion and vie to take stage center in the ongoing chorus of praise.

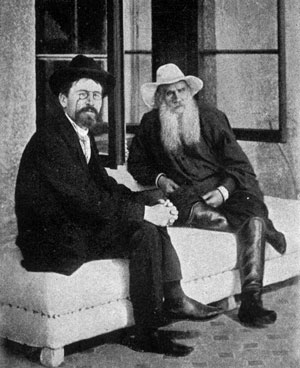

Chekhov with Tolstoy

Daily Chekhov – (twitter)

Lady with the Dog/ Дама с собачкой – 1/9 (see a great classic on youtube)

Many versions of theatrical productions now on view on youtube..Judi Dench in the Cherry Orchard etc.

ANTON CHEKHOV 1860 – 1904

His last words

‘It’s a long time since I drank champagne’

Terminally ill, he went with his wife Olga to Badenweiler. Later she recalled his dying moments: ‘Anton sat up unusually straight and said loudly and clearly (although he knew almost no German): “Ich sterbe” (I’m dying). The doctor calmed him, took a syringe, gave him an injection of camphor, and ordered champagne. Anton took a full glass, examined it, smiled at me and said: “It’s a long time since I drank champagne”. He drained it, lay quietly on his left side, and I just had time to run to him and lean across the bed and call to him, but he had stopped breathing and was sleeping peacefully as a child … ’

Update:The Russian playwright seems as modern to audiences and writers as ever – and also as mysterious

Chekhov is different; what does he think of his characters? Does he admire them or pity them? Ask us to examine or ridicule? It’s never obvious. Chekhov’s characters tend to let their mouths run away with them (Gayev in The Cherry Orchard fills a silence with an idiotic hymn of praise to a bookcase that, even as he’s saying it, he must regret). It’s almost as if Chekhov lets silences form in his play, which his characters nervously fill and thus reveal themselves.