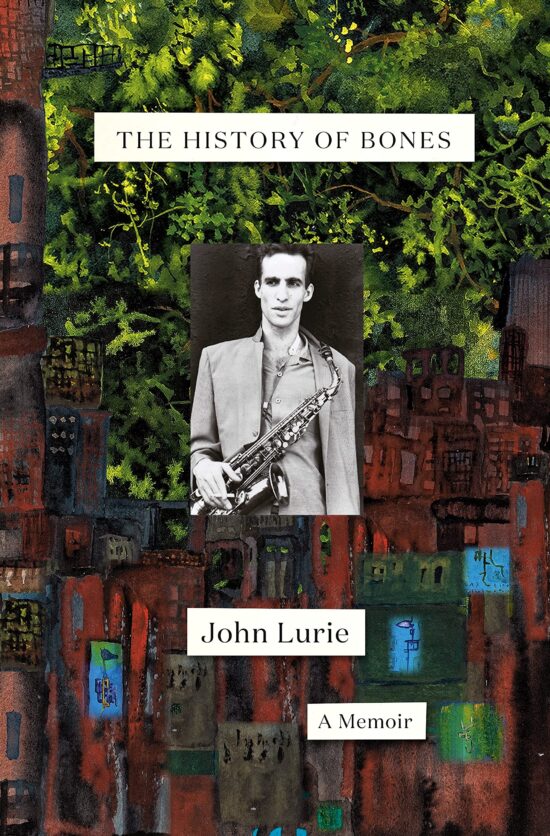

A Memoir, The History of Bones – by John Lurie

Tuesday, December 14th, 2021

(Happy birthday John Lurie – December 14)

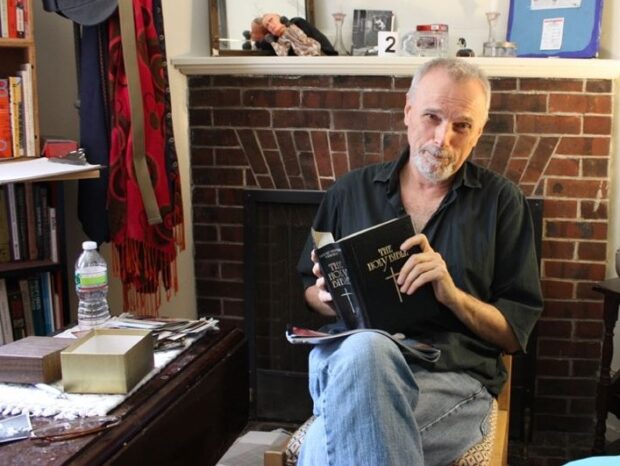

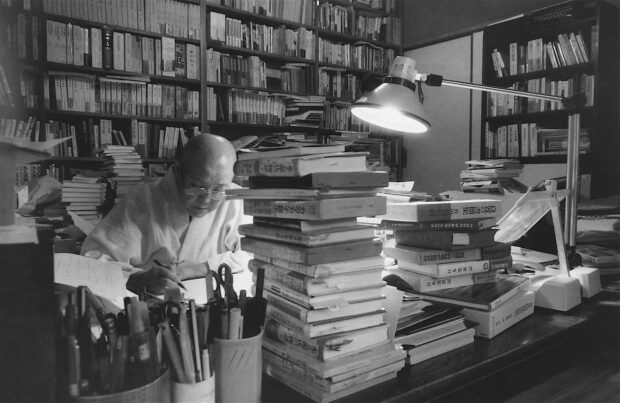

John Lurie’s father used to take him to fishing. John Lurie is a hard working, self taught artist in music, acting and in painting. Basquiat painted and slept at his place. Basquiat was a close friend that Lurie wrote a lot about in this memoir.

John Lurie is a world traveller.

He wrote about Africa, one of many places Lurie visited. He wrote.

“I had been depressed for a long, long time. I could not get out of it. Africa saved me. You can feel life started there.

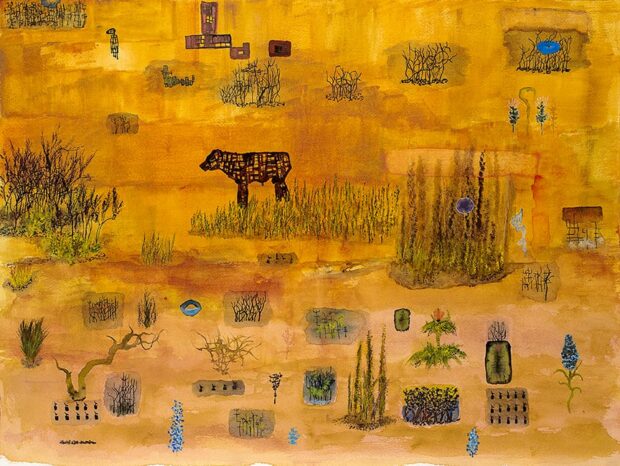

More paintings at his Gallery with great soundtrack from John Lurie’s Strange and Beautiful homepage

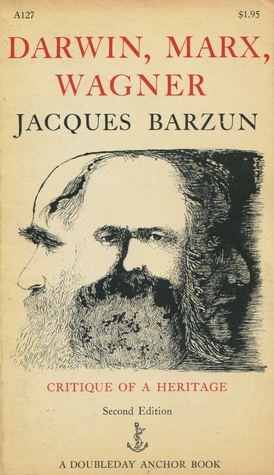

Strange and Beautiful John Lurie (previous post)

Listen to his playing here (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=N_864xjMQY8)

John Lurie: ‘I wanted to break into Martha Stewart’s house and change the curtains. My lawyer said no’

(He’s hung out with Warhol and gone ice fishing with Willem Dafoe, but the Fishing With John man’s new series stars just him and his canvas)

(A man, a bull and of course, the Soldier Bunnies. – John Lurie)

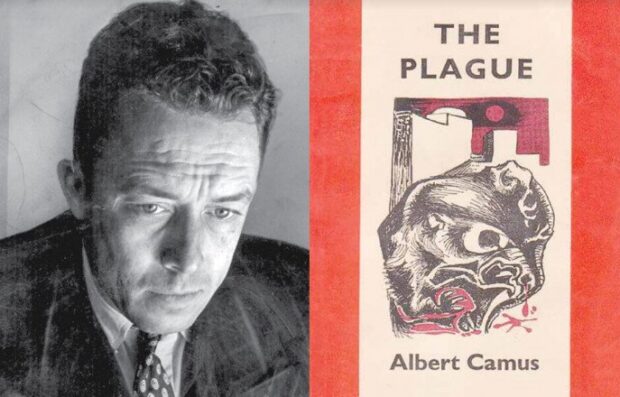

and Maria Casarès

and Maria Casarès