Scottish odyssey

The Places In Between, Rory Stewart, 2006

I first discovered the Scotsman Rory Stewart on the Bill Moyer’s Journal. Rory Stewart is now director of the Carr Center for Human Rights Policy at the Harvard Kennedy School of Government. Lynn Sherr introduced Stewart as advisor to both Secretary of State Hillary Clinton and U.S. Special Envoy Richard Holbrooke. The following is a small part of the transcript:

LYNN SHERR: What do you tell them?

RORY STEWART: Again, my message is: focus on what we can do. We don’t have a moral obligation to do what we can’t. People can get very fixed by saying, “But surely you’re not saying we ought to do nothing? Surely you’re not saying we ought to allow the Taliban to do this or that?” And I just keep saying “ought” implies “can”– you don’t have a moral obligation to do what you can’t do.

LYNN SHERR: How is your advice taken?

RORY STEWART: I think what I see at the moment is that people are polite, because they imagine maybe I have some experience with Afghanistan. But I’m one of a broad community of people — we have nine people working in my center at Harvard who’ve worked there for 20 or 30 years and the problem we all have is that if the Administration has for some reason already decided that they’re going to increase troops, they’re going to do a counterinsurgency campaign, it’s very difficult for them to take on board people coming back and saying, “Look, actually, I don’t think this is going to work. It’s a great idea. I can see why you want to do it. But by trying to do the impossible, you may end up doing nothing. I’d like to present an alternative strategy, which is lighter, more intelligent, and may end up actually achieving something.”

LYNN SHERR: And again, their reaction? They listen politely, you say?

RORY STEWART: They listen politely, but in the end, of course, basically the policy decision is made. What they would like is little advice on some small bit. I mean, the analogy that one of my colleagues used recently is this: it’s as though they come to you and they say, “We’re planning to drive our car off a cliff. Do we wear a seatbelt or not?” And we say, “Don’t drive your car off the cliff.” And they say, “No, no, no. That decision’s already made. The question is should we wear our seatbelts?” And you say, “Why by all means wear a seatbelt.” And they say, “Okay, we consulted with policy expert, Rory Stewart,” et cetera.

So much for being an expert today.

Rory Stewart’s biography sounds like fiction. Born in Hong Kong in 1973, he was educated at Eton and Oxford. He was tutor to Prince Harry and Prince William. In the 90’s he joined the Secret Intelligence Service and served in the embassy in Jakarta dealing with East Timor. He was next appointed British representative to Montenegro dealing with Kosovo.

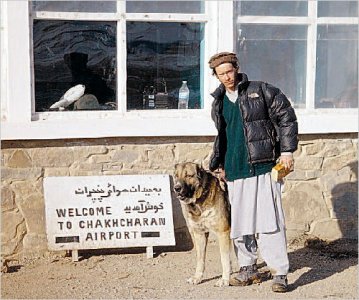

Rory Stewart in Afghan garb with Mastiff Babur

This book recounts a small part of an amazing walking journey historian Rory Undertook over 20 months to recreate the 1514 journey of Babur (descendant of Timur and Genghis Khan) from Samarkand, Uzbekistan to Kabul which he conquered. By 1527 Babur had conquered all of Northern India establishing the Mogul dynasty with Agra his capital.

Rory spent 16 months walking from Iran to Nepal. The government of Iran took his visa away and he was refused entry to Afghanistan by the Taliban so he resumed his journey in Pakistan, crossing to Katmandu where, in December 2001, he heard that the Taliban had fallen, so he returned to Herat to pick up his journey from Herat to Kabul. Babur had made his journey through the mountains in the dead of winter and Rory seemed to find the prospect of doing the same thing in 2002 appealing. U.N. workers called him “a nutter” for his walk which he took as a complement.

This book recounts the kind of travel that is far more common in Europe than in America. Herman Hesse in Narcissus and Goldmund describes a young man wandering around medieval Germany indicating that this coming of age European “Walkabout” has been a tradition for a long time. Overland trips from Europe to India and Nepal by motorcycle, van, and bus were common in the 1960s and 1970s but with the Iranian Revolution and Soviet Invasion of Afghanistan in 1979 such journeys died down. A recent German biopic, Eight Miles High, of Uschi Obermaier features a three year trip with boyfriend adventurer Dieter Bockhorn by customize bus from Germany to India in 1973. Their adventure lasted three years and was highlighted by their wedding, complete with elephants, in India. God seems to protect the young and naive which is why most young travelers, despite taking crazy risks, seem to come through relatively unscarred by the experience.

As if walking through the mountains alone in the dead of winter were not enough challenge, Rory somehow acquires a dog, a half wild, uncared for 140 pound mastiff of indeterminate age that he names Babur. So not only does he have to beg for food and shelter in each village for himself, he must find food and shelter for his huge dog in a culture where dogs are considered unclean. A boy who is in training to become a mullah informs Rory that the Koran declares dogs to be unclean. When Rory asks to see the passage, the boy says he doesn’t know where it is. “But haven’t you memorized the entire Koran in your studies? Yes, but it is written in Arabic and I don’t understand Arabic.” Like Roman Catholics who loved the Latin mass they cannot understand, this boy has memorized the entire Koran without understanding anything in it. In many villages he has to fight off with his walking stick packs of dogs sent by children to harass him and his dog.

The journey itself is pretty bleak. Rory walks in sub zero temperatures, through blizzards with zero viability, fighting to forge a path through waist deep snow, and trying to break through thick ice to reach drinking water. Through the first half of his trek, he follows the Hari Rud river, climbing to its source. In Herat, Rory collects a series of letters of introduction which he hopes will result in offers of hospitality along his route. This plan is quickly dashed as a village headman demands the letters (for his own use) and Rory discovers that the local head men are mostly illiterate so cannot write much less read such letters. He falls back on an oral tradition where he recounts the list of men who have recently offered him hospitality and memorizes the names of important men he is likely to meet at the next villages. To make life more miserable Rory suffers from constant dysentery and headaches. He tries to document his travels by writing in his journal, sketching people he meets (some are reproduced in the book) and taking very dark black and white film photographs in which the features of people pictured can hardly be made out.

From Herat he is accompanied by two security soldiers who are ordered to walk with him halfway to Kabul. Both are wearing American camouflage overalls and ill fitting boots which damage their feet. The leader is a congenital liar who introduces Rory as an Ukrainian (Soviet), American Spy, U.N. high official with millions to disperse to the local authorities. After the two start suffering from dysentery and foot sores, Rory is finally able to bribe them to leave him and they return to Herat. With the occasional local guide as part of local hospitality, Rory completes his walk largely on his own.

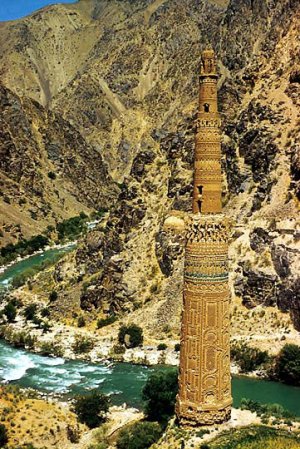

Minaret at Jam

Rory comes to the ancient city of Jam, destroyed by Genghis Khan. A lone minaret remains of what was once a major trading center. In the 1970s professional archeologists were busy excavating the historic city but the Soviet invasion forced them to leave and they have never returned. Rory encounters hundreds of local villagers randomly digging throughout the ruins looking for any artifacts which they will be able to sell to collectors for $1 or $2 dollars.

Rory’s route took through all four major ethnic groups making up Afghanistan. The Pashtun posed the biggest threat to Rory’s trek. When he asks village elders who they want to lead a new Afghanistan they invariably start by naming their local strongman. When Rory persists, they all mention Ahmed Shah Massoud the Tajiks fighter assassinated by al Qaeda. When he asks their opinion of Hamid Karzai, the most remote villagers immediately respond that Karzai is America’s puppet.

Stewart encounters more U.N. and other aid workers and writes one the best accounts of this new breed that I have seen anywhere (as a footnote):

Critics have accused this new breed of administrators as neocolonialism. But in fact their approach is not that of a nineteenth century colonial officer. Colonial administration may have been racist and exploitative, but they did, at least work seriously at the business of understanding the people they were governing. They recruited people prepared to spend their entire careers in dangerous provinces of a single alien nation.They invested in teaching administrators and military officers the local language. They established effective departments of state, trained a local elite, and continued the countless academic studies of their subjects through institutes and museums, royal geographic societies, and royal botanical gardens. They balanced the local budget and generated fiscal revenue because if they didn’t their home government would rarely bail them out. If they failed to govern fairly, the population would mutiny.

Post-conflict experts have got the prestige without the effort or stigma of imperialism. Their implicit denial of the difference between cultures is the new brand of international intervention. Their policy fails but no one notices. There are not credible monitoring bodies and there is no one to take formal responsibility. Individual officers are never in any one place and rarely in any one organization long enough to be adequately assessed. The colonial enterprise could be judged by the security or revenue it delivered, but neocolonialists have no such performance criteria. In fact their very uselessness benefits them. By avoiding any serious action or judgment they, unlike their colonial predecessors, are able to escape accusations of racism, exploitation, or oppression.

Perhaps it is because no one requires more than a charming illusion of action in the developing world. If the policy makers know little about the Afghans, the public knows even less, and few care about policy failure when the effects are felt only in Afghanistan… A year before they had been in Kosovo or East Timor and a year later they would be in Iraq or offices in New York and Washington.

Murad Khane District of Kabul

A year after his Afghan trek, Rory Stewart was appointed Coalition (civilian) Deputy Governor of Maysan and Senior Adviser in Dhi Qar, two provinces in southern Iraq. From this experience he penned his second book The Prince of the Marshes: And Other Occupational Hazards of a Year in Iraq. For this he was made an Officer of the Order of the British Empire at age 31. In 2005, he founded an NGO, the Turquoise Mountain Foundation and spends much of his time in Afghanistan. Chalk one up for the neocolonialists.