Eric Holder: Too Big to Jail

The Divide; American Injustice in the Age of the Wealth Gap, Matt Taibbi, 2014

A painful book full of well researched stories from both ends of the injustice spectrum; from wall street to welfare to stop and frisk to immigrant extortion and deportations.

At the center of the failure to try or jail a single financial bankster is Attorney General Eric Holder, author during the Clinton administration of the infamous Collateral Consequences doctrine at the heart of the current “too big to jail” policy. This then is the bookend to the story of Timothy Geithner’s refusal to break up Citibank or any other too big to fail institution. See She Bear at the FDIC. As with Geithner, Taibbi makes a strong case for cowardliness at the heart of each failure. This is in sharp contrast to the effective government action to deal with the savings and loan crisis of the 1980s where many executives were sent to jail and were banned for life from banking. See William Black’s account.

Collateral Consequences doctrine dictates that no prosecution should be undertaken where innocent bystanders like stockholders and corporate employees or global financial stability may be adversely effected. In effect, this vague, undefinable “doctrine” has prevented any and all government prosecutions from proceeding. Instead, the government has negotiated an endless stream of financial “settlements” where the corporations agreeing to the settlement admit to no wrong doing, no one gets fired, and no one has to face future litigation. At its highest in the case of JP Morgan the total settlements amounted to 12% of one year’s profits. The target institutions have come to look at these “settlements” as a normal cost of doing business as usual. The underlying criminal behavior continues.

The most notorious and disgusting cases were the The HongKong and Shanghai Bank HSBC settlement for mafia and drug cartel money laundering and the LIBOR interest fixing settlement involving many banks. If these cases do not involve criminal activity then what does. Oh, I see, it is criminal to stand on the sidewalk outside your own apartment. This is the type of contrast Taibbi is exposing.

Less emphasized in this book but equally true, most of these bankster “settlements” have gone directly into government coffers. Those victimized by the fraud receive nothing or laughable amounts. The bank illegally repossessed and sold your house? Here’s $200, now go away.

How about the whistle blowers like the woman at JP Morgan Chase fired because she blew the whistle on robo-signing for credit card collections. All the government can seem to do after several years is to continue to “lose” her whistle blower’s case file. She doesn’t even know if she is on file.

For lighter entertainment, Taibbi includes the case of several big time short sellers (see also the Big Short) who wrongly guess that a well run Canadian insurance company is about to go out of business and then hire some clowns to try to force them out of business with dirty tricks. When this fails, the insurance company sues the short sellers for damages but of course the Canadians lose the case.

Then there is the interesting case of the Barclay Bank buying the husk of Lehman Brothers after the government (read Hank Paulson) refuse to bail them out forcing Lehmans into bankruptcy. Barclay masterminds a clever scheme to secretly reduce the $50 Billion asset purchase by $5 billion by tricking the judge with an amendment. When the Lehmans creditors discover the scheme and sue, the same judge that was fooled during bankruptcy hearings buys a weird McNamara like “Fog of War” defense, this time called the “Fog of Bankruptcy” that during hurried bankruptcy filings “shit happens”. Too bad, no relief for the creditors.

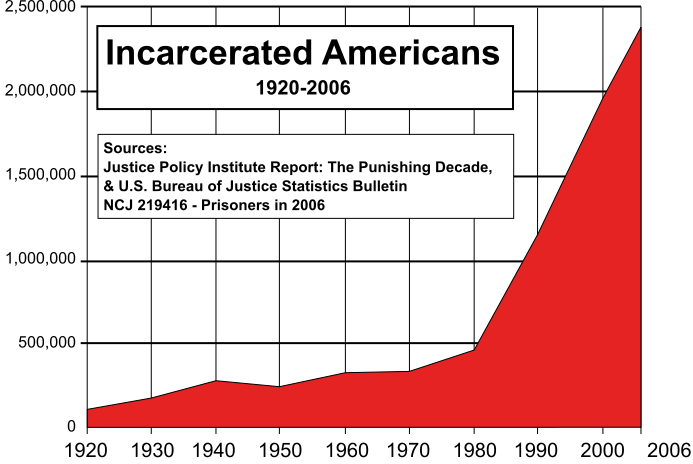

Want to invest in a growth industry? Try private jailers. Note that the sharp increased slope starts with Reagan but does not slow for Clinton.