Communist Chinese Misfit

Confessions: An Innocent Life in Communist China, Kang Zhengguo, 2007

A biography and history of Communist China from the Mao revolution of 1949 to the present through the life of a stubborn, naive, innocent young man who wanted only to be left alone to study ancient Chinese literature, to write about it, and maybe teach. Instead, two innocent letters drew him down the rabbit hole from college to a brickworks laborer to a labor prisoner to a forced labor orchard worker to an adopted peasant with a peasant wife and family.

Xi’an Bell Tower<>

Hua San near Xi’an

Kang grew up in Xi’an the capital of Shaanxi province and one of four capital cities of ancient China. Kang’s father was a heroin and alcohol addict but remained a fully employed engineer. His mother was a college graduate and full time teacher. Kang spent much of his childhood in the two acre Silent Garden home living with his respected Buddhist grandfather who supported the Communist revolution and saw Communism and Buddhism as compatible. Initially his grandfather held important committee positions in the local party. It was his grandfather’s personal library that led Kang to his lifelong long of ancient Chinese literature.

Things seemed all right for the family until the Great Leap Forward campaign of 1958 after which there was widespread famine and purge after purge, slowly reducing his “landlord” family to increased hardship and poverty. For a time, his grandfather was forced into a tiny apartment but when the owner wanted it back he was returned to a small space in Silent Garden which was allowed to fall into ruins. The most disastrous campaign after the Great Leap Forward was the 1966 Cultural Revolution. This campaign effectively closed schools for ten years and an entire generation of Chinese grew up without much education. It also resulted in sending record numbers of city people to the countryside, some of which were never able to return.

Dr Zhivago

Dr Zhivago

Kang was a mischievous child and so-so student but was accepted to Shaanxi Normal University. When another student in trouble with the authorities was discovered with a letter from Kang, Kang was expelled from College and forced to work in a primitive brickworks. He taught himself Russian and read any Russian literature he could find. When Doctor Zhivago was published, he naively wrote to a university in Russian asking to borrow a copy. This letter got him three imprisonment with forced labor. The title Confessions refers to the numerous confessions and struggle sessions he was forced to undergo. The hardened prisoners helped him learn not to give up information the authorities didn’t already know and to write minimal confessions needed to survive. After release from prison, he was unable to find work in Xi’an and was forced into a job at a remote orchard. While his family suffered greatly from the Cultural Revolution, Kang himself was going through his own nightmare and had little contact with the rampaging students.

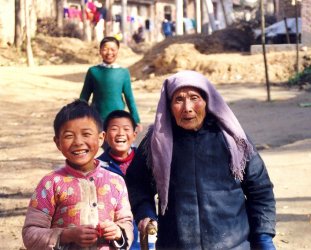

Shaanxi Peasants<>

Shaanxi Wheatfields

The book spends a lot of time on the residency registration system which forces everyone to stay where they are registered. The system allowed the regime to keep peasants away from the cities and to exile dissidents to the countryside where they would be unable to return to the cities. Kang was registered in Xi’an, but without hope of finding work, he was a burden on his family. They attempted to arrange a marriage with a peasant girl but could find no-one willing to marry a former political prisoner. Finally they located an old bachelor, in 1972, who was willing to adopt Kang, then 28 years old. This allowed Kang to change his name and become a peasant, hopefully escaping his past. Several years later he married a peasant girl and they had two children. In preparation for his life as a peasant Kang studied clock and electric motor repair in Xi’an before moving to the village. These skills allowed Kang to travel to other villages and supplement the communes meager pay.

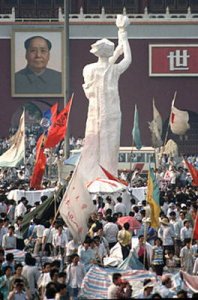

Tianamen Square Protest

Finally Mao died in 1976 and subsequent reforms allowed Kang to return to Shaanxi Normal University and have most of his dossier purged. As a graduate student, the ever non conforming Kang chose to write his thesis on an ancient erotic work. His advisor failed him and refused to allow him to graduate. He kept appealing and eventually was allowed to graduate and was later granted his masters degree. Kang taught English at Jiaotong University. In his usual naive blundering fashion, towering over other protesters and appearing clearly in the photos wearing a headband reading “Aim Your Guns Here“, Kang protested the Tiananmen Square massacre of 1989. Kang had managed to keep and listen to short wave radio through much of his ordeal and kept up with events across the country during these protests via radio.

He published a monograph, A Study of Classical Chinese Poetry on Women and by Women, and in 1990 received a letter from Professor Chang of Yale University praising the work. In 1991 Yale University invited Kang to participate in a conference on Women and Literature in Ming-Qing China to be held in 1993. It took Kang the full two years to get the passport and documents needed to attend the conference. Professor Chang turned out to be a woman. Kang returned to China after the conference to the amazement of his friends.

In 1994 Yale invited Kang to become a Chinese language teacher at Yale. To get the documents this time, Kang had to quit his job and give up his apartment before authorities would consider his application. He wanted to bring his family this time and Yale sent documents to support this. The American embassy in Beijing at first refused a visa for Kang’s 18 year old daughter, but Yale pressured them to relent. His wife adjusted well, first working in a day care center, then getting a job at a surgical supply manufacturer in New Haven. His children also adjusted well and have done well in America, which Kang considers his best legacy.

This work is also a reminder that China hasn’t changed much today in human rights terms. Kang was detained for several days in 2000 during his last trip to China for an academic conference. His Tiananmen Square protests and correspondence with friends again came back to haunt him. If not for the pressure from the president of Yale through the State Department, he might have disappeared down the rabbit hole again. After this experience, Kang became an American citizen. Kang points out that economic interests keep human rights news of China to a minimum and we tend to forget how repressive the regime still remains. His conclusions about modern China:

I took these clandestine scenes (illegal mahjong gambling) as a metaphor for the Chinese society in the post-Mao, post-Deng era; it was a large-scale producer of material, spiritual, and even human garbage, hidden behind a curtain of propaganda.

Good thing he no longer goes to China.

For a more detailed indictment of Mao Tse Tung’s reign June Chang, author of Wild Swans, has written Mao: The Unknown Story. see