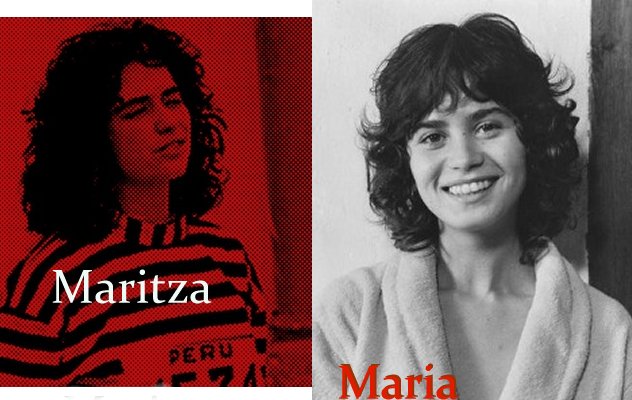

Maria and Maritza

What are you running away from? (In the Passenger Maria was quiet, intelligent, even sweet.)

Adieu Maria Schneider, 1952 – 2011

Daniel Gelin was her father who never acknowleged his paternity.

Pauline Kael on The Last Tango in Paris

The role is said to have been conceived for Dominique Sanda, who couldn’t play it, because she was pregnant, but surely it has been reconceived. With Sanda, a tigress, this sexual battle might have ended in a draw. But the pliable, softly unprincipled Jeanne of Maria Schneider must be the winner: it is the soft ones who defeat men and walk away, consciencelessly. A Strindberg heroine would still be in that flat, battling, or in another flat, battling. But Jeanne is like the adorably sensual bitch-heroines of French films of the twenties and thirties—both shallow and wise. These girls know how to take care of themselves; they know who No. 1 is. Brando’s Paul, the essentially naive outsider, the romantic, is no match for a French bourgeois girl.” – Pauline Kael (via cinema viewfinder)

Maria had a breakdown after the release of “Last Tango in Paris” (New Yorker)

Scroll down to read what Bertolucci said and what Maria said about her trauma she suffered from making the film.

Mario A. posted many images from the most intimate and vulnerable film stills from the Last Tango in Paris.

“Schneider gained a reputation for unreliability, and walked off several movie sets. She showed some taste in abandoning Tinto Brass’s Caligula (1979), but she also left That Obscure Object of Desire (1977) after three weeks of shooting — reportedly in protest at the amount of nudity — so that Luis Buñuel, with surreal logic, decided to cast two women in the role of Conchita.

A few weeks ago the image of Maritza came to this reader’s attention as a possible doppleganger of Maria Schneider.

Dancer Upstairs trailer (directed by J. Malkovich) was modeled after Maritza who is currently serving her term in prison.

It’s a powerful experience to meet a person you have lived with intimately in your head, whom you have had to construct from other people’s memories. I know what Maritza’s Argentine husband Saúl Mankevic thought of her; her poet-lover Rafael Davila; her director at the Ballet Naçional, where she danced Prokofiev as a Cinderella fairy. “She could have been the best ballerina in Peru,” said Vera Stastny. But what I have never been able to work out—perhaps a reason for writing a novel and screenplay about her—is the process that led Maritza one day to exchange the ballet for the bullet.