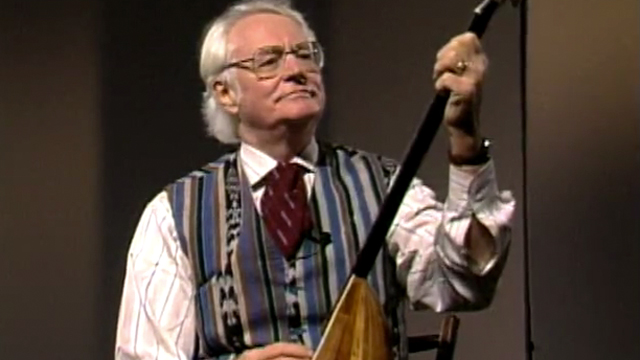

Charles Simic A Poet from Belgrade, The World Does not End

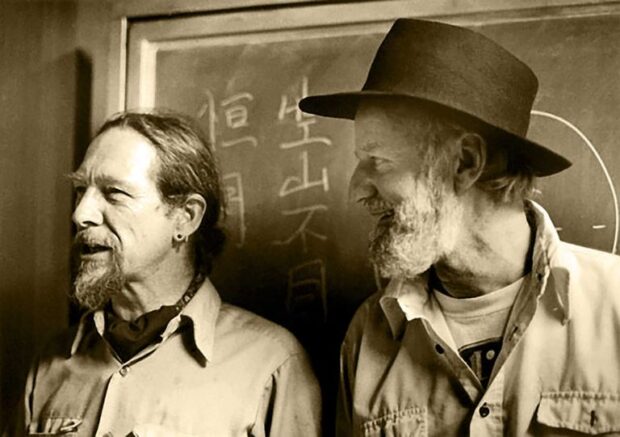

Tuesday, January 10th, 2023(Photo via )

“History is a cookbook. The tyrants are chefs. The philosophers write menus. The priests are waiters. The military men are bouncers. The singing you hear is the poets washing dishes in the kitchen.”

— Charles Simic

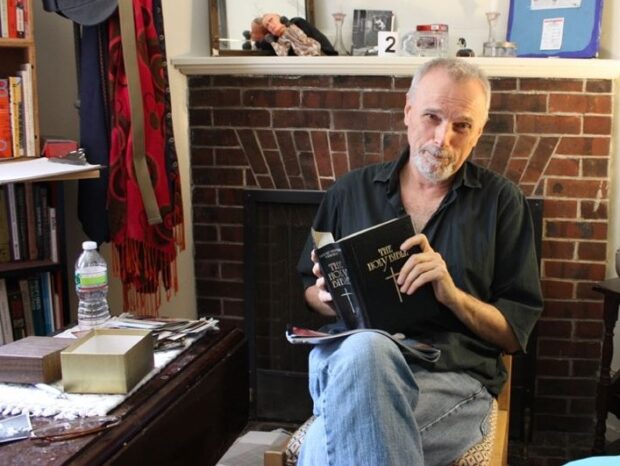

Charles Simic Pulitzer Prize winning poet dies at 84

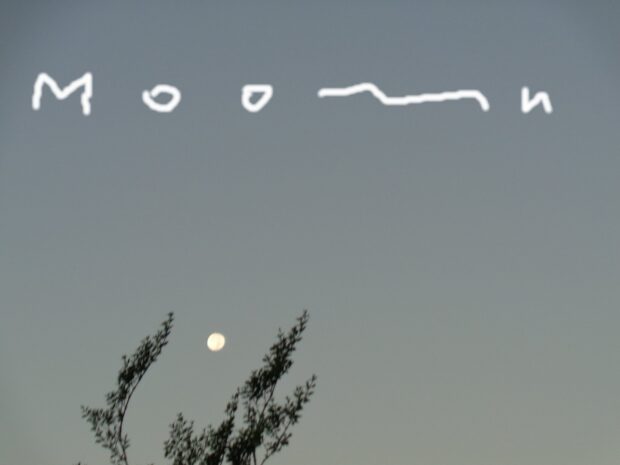

There Is Nothing Quieter

By Charles Simic

February 1, 2021

Than softly falling snow

Fussing over every flake

And making sure

It won’t wake someone.

Published in the print edition of the February 8, 2021, issue, The New Yorker.

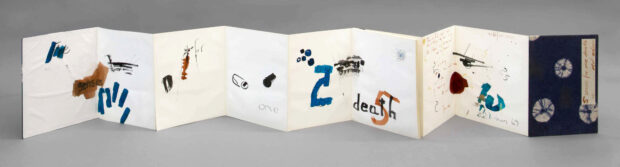

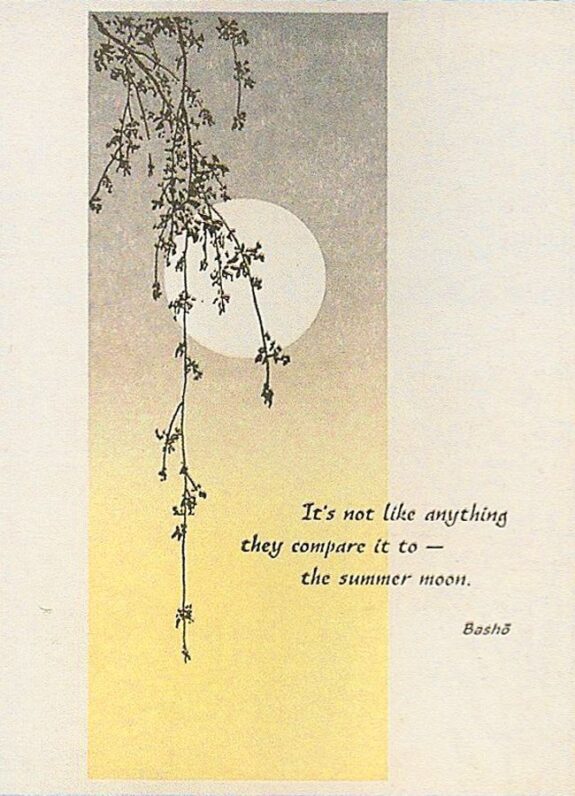

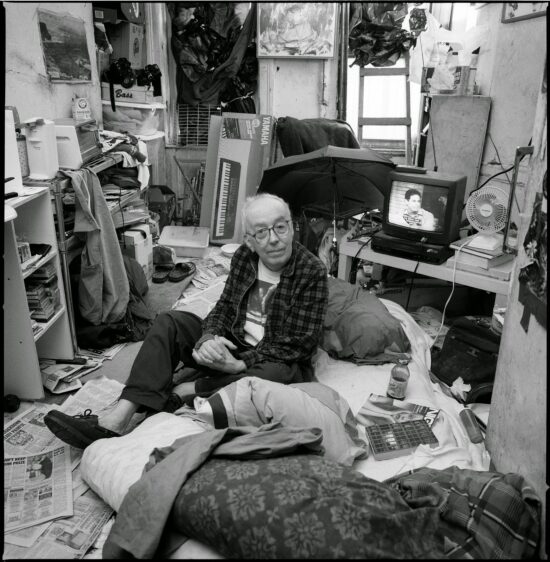

Author of dozens of books, Simic was ranked by many as among the greatest and most original poets of his time, one who didn’t write in English until well into his 20s. His bleak, but comic perspective was shaped in part by his years growing up in wartime Yugoslavia, leading him to observe that “The world is old, it was always old.” His poems were usually short and pointed, with surprising and sometimes jarring shifts in mood and imagery, as if to mirror the cruelty and randomness he had learned early on.

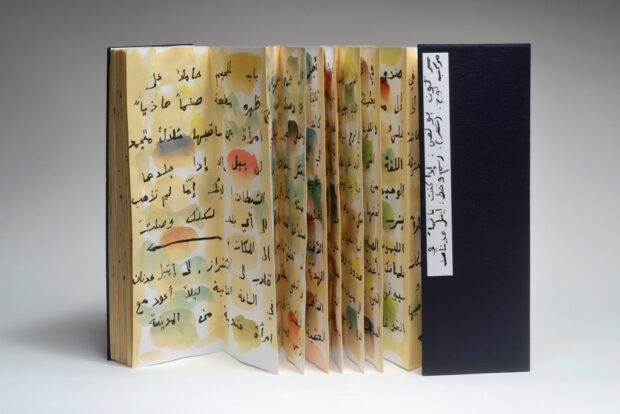

His notable books included The World Doesn’t End, winner of the Pulitzer in 1990; Walking the Black Cat, a National Book Award finalist in 1996; Unending Blues and such recent collections as The Lunatic and Scribbled in the Dark. In 2005, he received the Griffin poetry prize and was praised by judges as “a magician, a conjuror”, master of “a disarming, deadpan precision, which should never be mistaken for simplicity”. He was fluent in several languages and translated the works of other poets from French, Serbian, Croatian, Macedonian and Slovenian.

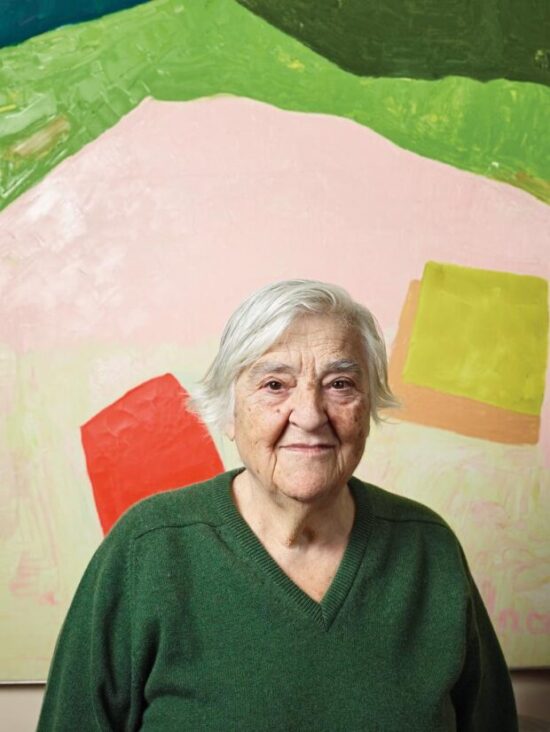

In 1964, Simic married the fashion designer Helene Dubin, with whom he had two children. He became an American citizen in 1971 and two years later joined the faculty of the University of New Hampshire, where he remained for decades.His first book, What the Grass Says, came out in 1967. He followed with Somewhere Among Us a Stone is Taking Notes and Dismantling the Silence, and was soon averaging a book a year. A New York Times review from 1978 would note his gift for conveying “a complex of perceptions and feelings” in just a few lines.

“Of all the things ever said about poetry, the axiom that less is more has made the biggest and the most lasting impression on me,” Simic told Granta in 2013. “I have written many short poems in my life, except ‘written’ is not the right word to describe how they came into existence. Since it’s not possible to sit down and write an eight-line poem that’ll be vast for its size, these poems are assembled over a long period of time from words and images floating in my head.”