The Big Myth; How American Business Taught us to Loath Government and Love the Free Market, Naomi Oreskes and Erik M. Conway, 2023

Merchants of Doubt Movie 2014

<> <> <> Nierenberg <> <> <> <> <> <> Seitz <> <> <> <> Singer <> <> <> <> <> <> Ebell

(In Merchants of Doubt, 2010 featuring Bill Nierenberg, Fred Seitz, Fred Singer, Myron Ebell) we stumbled across the story of four physicists who laid the foundations for climate change denial as far back as the late 1980s. These men were prominent scientists—one was a former president of the the U.S. National Academy of Sciences, another headed a major NASA lab—so it wasn’t remotely plausible that they didn’t understand the facts. We discovered that they hadn’t just rejected climate science but had fought settled science on a host of public health and environmental issues, starting the the harms of tobacco. Two of these four scientists had worked with tobacco companies. (Why?) The right answer was ideology: market fundamentalism.

These men feared that government regulation of the marketplace—whether to address climate change or protect consumers from lethal products—would be the first step on a slippery slope to socialism, communism, or worse. This fear was rooted in their personal histories designing weapons systems in the Cold War. On behalf of the U.S. Government, they had worked to build the atomic bomb, the hydrogen bomb, and the rockets and submarines to deliver those weapons. They saw the Soviet threat as serious, a threat they had to help “contain”. When the Cold War ended, they couldn’t stop fighting. Instead they found a new enemy—environmentalism–which they viewed as a back door to socialism, if not communism. As one of them put it, “if we do not carefully delineate the government’s role in regulating…dangers there is essentially no limit to how much government can ultimately control our lives.”…So these men would do whatever they could to prevent government regulation of the marketplace, even if it meant fighting facts, challenging hard-won knowledge, and betraying the science they had helped to build.

Market Fundamentalism is not just the belief that free markets are the best means to run an economic system but also the belief that they are the only means that will not ultimately destroy our other freedoms. It is the belief in the primacy of economic freedom not just to generate wealth but as a bulwark of political freedom. And it is the belief that markets exist outside of politics and culture, so that it can be logical to speak of leaving them “alone”.

Milton Friedman, America’s most famous market fundamentalist, went so far as to argue that voting was not democratic, because it could be so easily be distorted by special interests and because in any case most voters were ignorant.

Because (Morris Llewellyn) Cooke and (Gifford) Pinchot put social considerations on par with—or perhaps even ahead—financial ones, critics accused them of being :communistic”, but neither man had a sympathy for communism or socialism Rather, they advocated a more rational form of capitalism than what Americans at that time had, in which the needs of the people would be a primary consideration and in which engineering decisions would be made by engineers rather than financiers. Cooke envisaged Giant Power as but one part of a “Great State”…placing the government of our individual states on a plane of effective social purpose.” We might call it “guidez-faire”: a form of capitalism in which government combated corruption, remedied market failure, and redressed social injustice.

What was radical about Giant Power was its reorganization of the entire system for generating and distributing electricity in Pennsylvania. Under Pinchot’s plan, the Giant Power Survey Board would be authorized to construct and operate coal-fired power plants, to mine the necessary coal, to appropriate land for mining, and to build and operate transmission lines, or issue permits to others to do so. Private operators could still function—indeed–the system would need them—but they would have to play by the rules and rates the board established. The board could also buy electricity from operators in neighboring states, or sell to them. Farmers could create rural power districts and mutual companies, and if the board chose to it could subsidize them”

The goals of Giant Power were socialistic in one important respect; the “chief idea” behind it was “not profit but the public welfare.” Its object was not “greater profit to the companies”, but “greater advantage to the people.” To make this happen, “effective public regulation of the electric industry” was an essential condition.

. When the Giant Power Survey Board’s report came out in 1923, industry leaders attacked both its contents and its sponsor. Immediately they mobilized to prevent Pinchot’s reelection. (He eked out a victory.) They also launched a disinformation campaign, using advertising, public relations, experts-for-hire, and academic influence to counter any suggestion that public management of electricity was desirable (much less necessary). Above all, the industry sought to discredit the very idea that the public sector could do anything more fairly or efficiently than the private sector. The goal was to strengthen the American people’s conviction that the private sector knew best, and to promote the idea that anything other than complete private control of industry was socialistic and un-American.

The Federal Trade Commission (FTC) held six years of hearings from 1930-1936 on a wide range of regulatory issues in the aftermath of the 1929 stock market crash that initiated the great depression, Their reports covered eighty volumes.

Economic historians William Hausman and John Neufeld: “private utilities led by [their] industry trade group the National Electric Light Association (NELA)…mounted a large and sophisticated propaganda campaign that placed particular emphasis on making the case for private ownership to the press and in schools and universities.” Historian David Nye: “The thousands of pages of testimony revealed a systematic covert attempt to shape public option in favor of private utilities, in which half truths and at times outright lies presented municipal utilities in a consistently bad light.” Historian Ronald Cline called the campaign “underhanded” and “unethical”.

The FTC found that industry actors had attempted to control the entire American educational system—from grade school to university—in their own economic interest. This effort focused on the social sciences—economics, law, political science, and government—but also included engineering and business. Its purpose was to ensure “straight economic thinking”–by which NELA meant capitalist free market principles—and to supply young people and their teachers with “correct information”. The goal was to mold the minds of the current generation and those to come…This was achieved, the FTC concluded through “false and misleading statements of fact, as well as opinions on public policy, found in reports and expert testimony of prominent university professors who are now discovered to have been in the pay of the private utilities.

The opinions NELA promoted were embedded in a larger argument that private property was the foundation not only of the American economy but of American life, so any attempt to interfere with the private operation of the electric industry threatened to undermine that way of life. Opinions to the contrary were denigrated as “unsound”, “socialistic”, and fundamentally un-American. The FTC found that the “character and objective of these activities was fully recognized by NELA and its sponsors as propaganda,” and that in their documents they “boasted that the ‘public pays’ the expense.”..the goal expressed outright in numerous documents—was to change the way Americans thought about private property, capitalism, and regulation.

On the surface NELA lost its fight. David Nye concludes that the “public revulsion that the NELA hearings caused put [rural] electrification back on the public agenda…and prepared the way for New Deal utility legislation.”

The United States today still has a predominantly private electric system (about 90 percent) that is less strongly regulated than in many other countries. On average customers of publicly owned utilities pay about 10 percent less than customers of investor-owned utilities and receive more reliable service. When attempts were made in the 1990s to deregulate the system entirely (California), it was a disaster for customers. The Enron company gamed the system before going bankrupt, and several of its executives went to jail for fraud, conspiracy, and insider trading. Electricity deregulation also proved a disaster for the people of Texas: when the state’s power grid failed in the face of an extreme winter storm in 2021, if left more than seven hundred head and somewhere between $80 and $130 billion in damages.

Since the crash of 1929, (National Association of Manufacturers) NAM had hemorrhaged members…The organization might have collapsed, but a new group of executives—mostly from large corporations—took over, with a bold idea to increase membership and their political power…NAM’s “education” efforts centered around a massive campaign to persuade the American people that big business’s interests were the American people’s interests. Americans needed to see that the real threat came not from “Big Business”, but from “Big Government”. While NAM took care to call the campaign “public relations” or “education” its goals were overtly political and mush of what was said was untrue.

Historian Richard Tedlow: “Unnerved by the impact of the depression, apprehensive of the growing strength of labor, enraged at critics of the failures of business, and rejecting almost in toto the devices of the new administration in Washington to find solutions to the problems inherited in 1933”, NAM leaders refused to engage in a serious attempt to identify the structural weaknesses, errors, and abuses that had contributed to the Great Depression, and honestly consider how they might be corrected. Instead, they turned to propaganda, spending millions to persuade the American people of the greatness of business and industry, and that the fault lay entirely with government and unions standing in the way of effective management.

NAM’,s radio series purpose: “The American Family Robinson seeks to emphasize the countless benefits which derive from living in a free country with CIVIL AND RELIGIOUS LIBERTY, REPRESENTATIVE DEMOCRACY, FREE PRIVATE ENTERPRISE.” The key claim of the NAM statement to the broadcasters hinged on the word inseparable; that freedom of speech and of the press, freedom of religion, and freedom of enterprise are inseparable.

In 1947, NAM put its weight behind (the Taft Hartley) bill…that banned many kinds of strikes, restored employer’s propaganda rights, barred union donations to federal political campaigns, and allowed state “right to work” laws…For the rest of the century, American businessmen would celebrate unregulated markets and corporate freedom, while disparaging any protection of workers, consumers, or the environment as government encroachment, even “shackles. They would insist that reforms intended to address market failures or defend workers were alien, un-American idea. They would decry “excessive” government spending on social programs, while accepting an orgy of military spending from which they would often benefit. Above all, they would develop and hone what in time became the mantra of American conservatism in the second half of the twentieth century: limited government, low taxation, individual responsibility, personal freedom.

All of this was definite strike against (Austrian Laissez-faire economist Ludwig von) Mises in FDR’s America, where the theories of the British philosopher and economist John Maynard Keynes dominated government offices and university departments. Keynes argued that the state had to manage the marketplace, to smooth out otherwise crushing business cycles and attend to needs not met by the private sector. Laissez-faire capitalism had produced devastating social evils—brutal child labor, deadly working conditions, poor public health, low education levels, an impoverished elderly population, and so on—as well as serious economic problems such as boom and bust cycles, widespread unemployment, and bank panics…In 1924, even before the Great Depression hit America, Keynes could credibly declare that the world had come to “The end of Laissez-Faire”…In his 1936 work The General Theory of Employment, Interest, and Money, Keynes dismantled the notion that markets were rational and could be trusted to restore prosperity.

Mises collapsed socialism into centralized planning…Was socialism indistinguishable from communism in this regard? Most Americans in the mid-twentieth century did not think so.

<> <> <> <> <> <> Thomas Friedman <> <> <> <> <> <> Frederick Hayek <> <> <> <> <> <> John Maynard Keynes

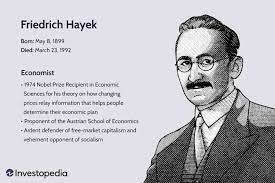

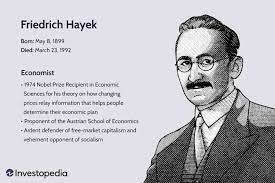

In the hands of ideologues, (Austrian Laissez-faire economist Friedrich August von Hayek’s) The Road to Serfdom was transmogrified from a complex and subtle argument about the risks of governmental control into an anti government polemic.

Added to the evidence free works of the Chicago school of economics was added the myth making novels of Ayn Rand (The Fountainhead Atlas Shrugged) and Laura Ingalls Wilder. (Little House on the Prairie).

Under Teddy Roosevelt and his successor, William Howard Taft, the federal government prosecuted several corporations, most famously Standard Oil. But within a few decades, the Chicago school was turning facts of history on their head, arguing that state power was the real threat, both to democracy and to capitalism.

With the publication of Capitalism and Freedom, Luhnow, Crane, Read, and Pew, along with their allies in NAM, the American Enterprise Institute, the Foundation of Economic Education, had their wish fulfilled. They now had the American version of The Road to Serfdom, their New Testament of market fundamentalism. Above all, they had what appeared to be a serious academic argument to transform their cruel and self-interested “opposition to unions and the welfare state from reactionary politics to good judgment in the public’s mind.” They had taken a self-interested and essentially unsubstantiated ideology—one with scant empirical foundation and bucket loads of available historical refutations—and transmogrified it into respectable academic theory. What had begun in the 1930’s as self-interested propaganda had been reconstructed as respectable intellectualism.

What (Ronald) Reagan carried forward from Mises, Hayek, and other twentieth century neoliberal thinkers was an unfalsifiable reverence for markets and hostility to government…It also underpinned one of the most disturbing (and ironic) aspects of the Reagan legacy: the rejection of information.

“Overregulation” was a libertarian construct linked to the myth of the indivisibility thesis and the metaphor of the road to serfdom…With the election of Ronald Reagan, market fundamentalists finally had the opportunity to put their ideology into practice, whether it was supported by facts or not.

In the 1970s, the idea gained a new name “supply-side economics”, because it would stimulate the economy not through government spending or increased consumer demand, but by boosting production…The resurrection of supply-side economics did not come from NAM however, but from a new economic guru: Arthur Laffer. tThe “Laffer Curve” was a graphical argument for a Goldilocks to taxation; rates that were too high would prevent investment in new production and or suppress the desire to work hard; rates that were too low would be inadequate to finance necessary government functions like law enforcement and national defense.

Supply-side economics—now referred to as Reaganomics—didn’t produce an American investment boom or surging tax receipts—neither did it produce the vaunted “trickle-down” effect. What it did demonstrably do was explode income inequality…The rich got richer, the poor got poorer, and the middle class treaded water. Supply-side economics was a shell game. The theory had been tested and failed. In a rational world, this should have discredited the idea and the economists who preached it. In 2019, this refuted theory earned Arthur Laffer the Presidential Medal of Freedom.

Lord Nicholas Stern, a former chief economist at the World Bank, would later (2006) call climate change the “greatest and most wide-ranging market failure” ever seen.

This (climate change) was a potentially fatal blow to the idea of the “magic of the marketplace”. At minimum it showed there were potentially enormous sacrifices associated with business as usual, evading the conventional cost-benefit analysis conservatives demanded to justify regulation. At maximum, it suggested that capitalism as practice threatened the future of life on earth.

Both Carter and Reagan worked to deregulate large swaths of the American economy, but Clinton, in some ways, went further, with dramatic deregulation of telecommunications and financial markets. In 1996, he declared that the “era of Big Government is over.”

Financial regulation—like telecom regulation—needed retooling for the twenty-first century. But instead of updating the relevant regulations Congress and the Clinton administration gutted them. The Gramm-Leach-Bliley Act (1999) effectively removed (repealed Glass-Steagall) the guardrails that for six decades had done the job they were built to do. When they were removed, the system crashed (2008).

All of this may make one wonder: was this ever really about capitalism? Or freedom? Or was it all just one long semi-continuous, shape shifting defense of the prerogatives of big business? Of freedom for capital and capitalists? Or had the market fundamentalists spent so much time defending the magic of the marketplace that they simply couldn’t accept market failure on a global scale? To accept the enormity of what climate change portended for civilization was to accept that capitalism as practiced, was undermining the very prosperity it was supposed to delivery. And not just in some distant future but now.

The conservative preoccupation with constraining government power has left us with a federal government too weak and too divided to handle big problems like Covid-19 and climate change. Even as the pandemic raged, millions of Americans refused to get vaccinated in large part because of distrust of “the government”, and the lion’s share of those American’s were political conservatives.