Patricia Highsmith with Arthur Koestler + Todd Haynes “Carol” inspired by Saul Leiter

Tuesday, January 19th, 2016<> <>

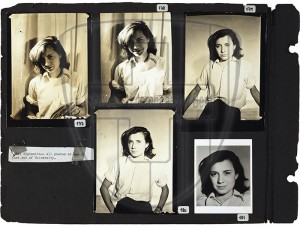

Patricia Highsmith – (Photo by Francis Goodman 1957)

Peter Wells on Patricia Highsmith

Koestler with writer Patricia Highsmith in Alpbach, Switzerland – on the day of the moon-landing, July 20, 1969. (The Swiss National Library)

She had a sort of romantic/intimate friendship with Arthur Koestler (who was married) but it was not presumed to be overtly physical.

Arthur Koestler (Kepler and Koestler)

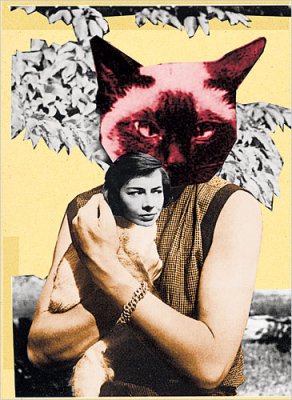

Choose your highsmith

Todd Haynes on Cate Blanchett, Saul Leiter and Queer Cinema

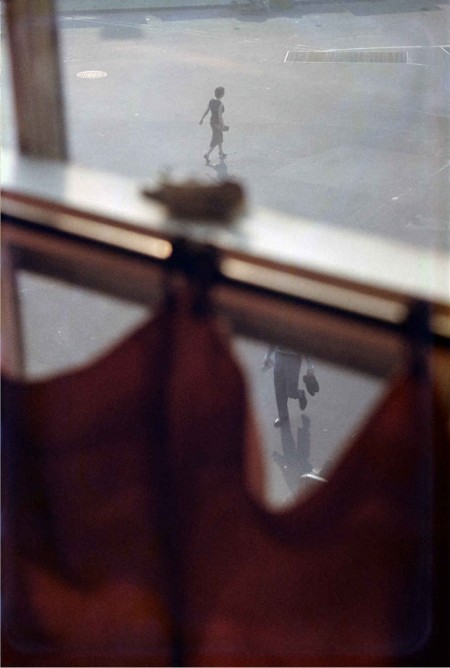

On the photographs of Saul Leiter…

“In Carol, we definitely keep returning to the predicament of looking as a visual strategy in how the film is put together. It was very conscious, as something that puts the subject on one side of the glass and the object on the other and filters their access to each. I think that visual language is a way of just revealing the act of looking as a predicament to begin with and one that is never completely easy to achieve. There’s always something in the way of what you want. [Saul Leiter] is a clear influence because he loved to do that and he did it so beautifully, disrupting his subject matter and finding planes of intersection and abstraction in his colour photography. While at times you think you’re looking at an abstract painting, it actually gives such a specific sense of time and place because of the kind of light and how it plays on glass and how it interferes with dust and dirt and grime. The real conditions of being in that city at that moment are revealed as palpable and beautiful and elemental in a way.”

See a video and photos Saul Leiter (1923-2013)

Todd Haynes Journey – Discovery

by Jeannette Winterson

by Jeannette Winterson